5 stars out of 5

Johnathan Glazer’s new film opens with black title credits on a white background. The colors dramatically invert when the title of the film appears. The words The Zone of Interest slowly, slowly fade to gray, continuing to black until they cannot be seen at all. The screen stays dark for what seems forever. Eventually, birds can be heard tweeting along with other sounds of nature, and you think the darkness of the screen will lift any second, but it doesn’t. You sit there slowly enveloped in the darkness, hearing sounds that cue you in that the image should be something else. You might even think it’s another instance to add to the list of failed film projection at the local theatre. And then after maybe two minutes of this, the image pops up of a family outside in what seems like the country. Green everywhere.

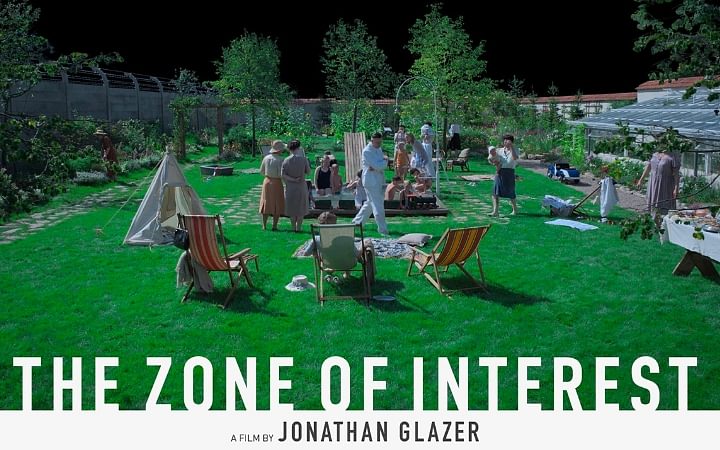

We are with the Hoss family enjoying a bit of countryside. The camera is relatively far behind the family, and we see only the backs of their bodies as they enjoy the river. This sets up a feel of a Maysles documentary. Very “fly on the wall” filmmaking. Rarely will the camera get closer than a full body shot and, if it does, it’s from the knees up, almost never a close up. Director Jonathan Glazer and cinematographer Lukasz Zal want us to be observers. They don’t want us to empathize. The Hoss patriarch Rudolf (Christian Friedel) is given one of our only knee-up close shots here. It is our typical hero framing for a Brad Pitt type, but he is anything but. His alabaster white skin, pouchy dad body, and unhip haircut are the opposite of whom we’re typically given this framing for. Everything is so bluntly mundane. The camera has no intention of telling us what is interesting, and the script and actors don’t feel at all pressured (or that much invested) in wanting to keep our interest. Which of course draws the viewer in for now because the viewer can’t help but realize how different this film is from a “normal” film. The family goes home. A pretty home. Green everywhere. We know we are in some past period from the clothes but not which period. The back yard has a pretty pool. Roses and other flowers abound. Then Rudolf gets dressed for work, and he is wearing a Nazi uniform. Even worse, we now realize that the beautiful wall adorned with vines and greenery is the only thing that separates the backyard from Auschwitz.

The film is about the mundaneness of evil, about living in the black. How you can know what is right and wrong, but somewhere you start compromising, and now you are living completely in black. Rudolf is one of the higher-ups at Auschwitz. A Commandant. Early in the film, he has a meeting explaining how each ZONE of the crematorium will work when they burn their victims. How one section is warming and burning while the other is cooling and being cleaned, and how it can continue this cycle efficiently. It’s with the same fervor perhaps as the local Best Buy manager telling his employees what to do with the space in the store previously occupied by physical media. Rudolf provides for his family, though. He has given them a lovely home. So what if his four children can hear the atrocities on the other side of the wall, such as one instance when their smallest boy can hear a Jewish man being beaten while soldiers are ordered to drown him in the river, and we helplessly watch this small child try to cope with it, whispering “don’t do that again.” He knows that he has heard something horrible, but his childlike mind clings to the learned behavior that the Jews have done something wrong in the first place--in this instance, fighting for an apple. His mind clings to anything that might take him out of this moment.

Rudolf’s wife Hedwig loves their life. She asks her husband to keep a look out for “goodies” such as chocolate when he takes the belongings of the new arrivals at Auschwitz. She brags about the diamond she found in toothpaste, and now she always has Rudolf bringing the toothpaste home. She talks of wanting to go back to that spa in Italy and shortly oinks like a pig with her husband. Our first good shots of Hedwig are of her looking at herself in the mirror at a new fur coat straight from the camp. Hedwig’s mother comes to visit, and Hedwig can’t wait to give a tour of their home and show off their lifestyle. Plenty of pastries are found on their dinner table though they are in a rationed Europe. She brags that her husband calls her the “Queen of Auschwitz.” Her mother comments on the wall, that the camp is just on the other side. Maybe her former neighbor is over there now. How she was so disappointed that she didn’t win the auction to her neighbor’s curtains that she loved so much. Hedwig responds that she is trying to grow more vines to cover the wall. The lie she tells herself, with green being used as a symbol for greed. Hedwig’s greed is the lie that makes the wall bearable.

The film only has two scenes of any real urgency (a rather low number for a film). One such scene is when Rudolf discovers he is being transferred and his wife argues for him to try to stay. When he tells her that isn’t possible, she then informs him that she and the kids will stay. She won’t give up her lifestyle. This is followed by Rudolf telling his family he is transferring and they are staying, saying, “The life we enjoy is worth the sacrifice.”

The other sequence of urgency happens rather unexpectedly. Rudolf has taken the two younger children in his new boat down the river. The kids are playing and swimming, and he is fly fishing a little farther down. It can’t help but be a little reminiscent of the peace and beauty in the film A River Runs Through It. And then suddenly, something touches Rudolf in the water. He reaches down and pulls up what seems to be a human jawbone. The river must be a dumping ground for Auschwitz. He makes a mad dash to get the kids out of the water, back home, and scrubbed down as furiously as he can. A very Lady Macbeth “out damn spot” moment.

Rudolf reads fairytales to his children at night, such as “Hansel and Gretel.” During this narrative, the image switches to a film negative of their Polish servant riding her bike to hide apples behind the shovels the Jewish prisoners use or in the trenches they dig, hoping they will find them and gain some nourishment. The girl at one point waits for some Nazi soldiers and a huge pig following them to cross before she goes to leave her apples. Black and white feature largely in the color palette of this film for obvious reasons. She is bright white because of the film negative, and everything else is black and gray but seems off, ethereal, a fairytale like look. Unfortunately, these sequences are the stark reality of the situation, and the evil witch being burned alive to save the children is the fairytale.

The film is a World War II drama, but filmed unlike any you have ever seen. There is nothing “flashy” about this film. For instance, this film is devoid of any impressive aerial shots with IMAX cameras. No big monologue scripted moments of Liam Neeson taking out his pen and saying, “This pen could have bought one life.” No great scene-chewing Nazi performances from the likes of Christolph Waltz or Ralph Fiennes. The film, despite being a WW2 drama, feels as far from Oscar bait as it could get. It feels more like a documentary, and was filmed very close to one. Practically no close ups. Reportedly 10 cameras were embedded in and around the house and kept running simultaneously. Johnathan Glazer called this process “Big Brother in the Nazi house.” This process leaves a mark on the performances, as they feel incredibly naturalist. Nothing that will be up for an acting Oscar, unfortunately, but something that should be praised and admired all the same. Probably the biggest snub of the “Best Ensemble Cast” award at the SAG’s. The lighting is all practical or natural light because Glazer did not want to “aestheticize” Auschwitz or the Nazis. A feat easier said than done when considering that the Nazi uniform has such an impressive design that it is a default template for many other iconic costumes such as the helmets of Darth Vader and his Stormtroopers. Special mention must be paid to production designer Chris Oddy who converted a derelict home beyond the Auschwitz camp wall into a replica of the Hoss home. The dress worn by the Polish girl is the real dress of the person the character is inspired from, and the sheet music she finds hidden near the shovels, and later plays, is music the real Alexandria found. Please Mr. Glazer, don’t make us wait another ten years for your next film.